"Southeast Asia has a real grip on me. From the very first time I went there, it was a fulfillment of my childhood fantasies of the way travel should be." Anthony Bourdain

As preposterous as it sounds, a bumpy, 14-hour ride through the African bush was my first introduction to South East Asia.

On that rough ride in a limping, broken-down Land Rover, a fellow passenger began to spontaneously recount his experiences living and working in Indonesia, and travelling the South East Asian region.

His stories were so vivid, his feelings about the region so strong and passionate, that by the time we had reached our destination, the Botswana capital Gaborone, I knew I would venture out to explore that part of the world.

My first trip to South East Asia was in 1985, a month travelling public transport to areas of Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia. I became totally hooked.

The rich and in some cases exotic cultural landscapes, the warm, inviting people, the high energy and dynamism, the colourful festivals, and the life-on-the-streets, attracted me then as they do now.

Successive annual trips eventually led to a move to Thailand in 1991, to take up a position in Chiang Mai and then Bangkok, the association with the country stretching back over 35 years.

HUHEHOT, CHINA, 1980

Working in Harbin, far in the north of China, in the early 1980s was like living in a time-warped bubble. There was then a strong feeling of isolation to the place, of non-connectedness to anywhere else on Earth.

What first springs to mind decades later are memories of the intolerable cold weather, the icy streets - stomped upon by legions of people in warm cotton boots, crumbling Russian architecture, Russian-style bread, the stench of rotting cabbage in apartment building hallways, scores of people crowding around us in a department store - curious about these strange-looking creatures, the grey and dank air - polluted by the ubiquitous coal-fired furnaces that kept the cold at bay, hidden underground Christian churches, our tiny transistor radio that connected us to BBC News and the world at large, and a fantastic January ice festival, where huge figures and structures were carved from blocks of ice taken from the frozen river.

Those were the early years when foreign investors were being courted, and tourism encouraged, though at that time visitors could only travel to twelve designated cities – everywhere else was off limits and required lengthy official paperwork.

Public prayer and worship were forbidden, and those who chose to disobey these restrictions could face a loss of job or housing, as well as ostracism.

Yet in Huhehot, Inner Mongolia, historically and religiously linked to Tibet, Buddhist temples seemed active, though clandestinely so.

A peasant woman bundles thatch on a cold winter day.

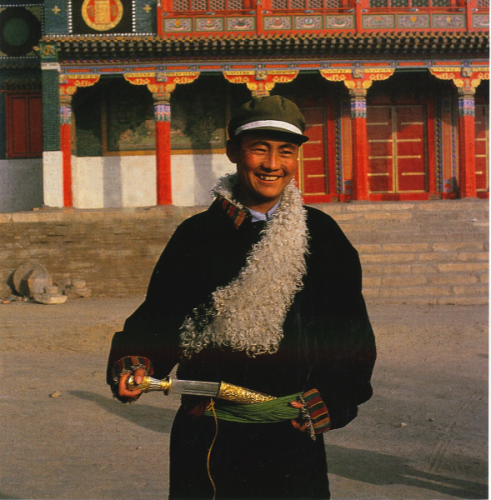

A Tibetan man, traditionally dressed replete with personal dagger, prepares himself for the long journey from Huhehot to Lhasa.

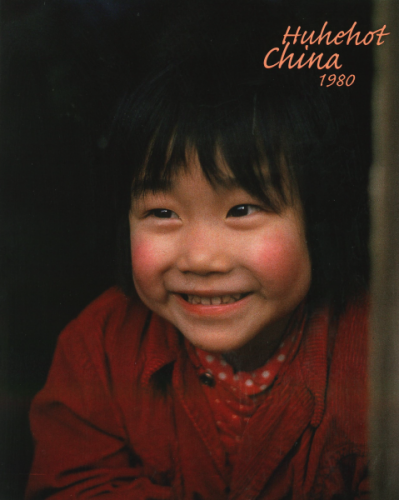

The joy and happiness of this lovely little girl illuminates the windows of her Huhehot home.

HANOI, VIETNAM, 1993

Travelling Vietnam’s north-south road, crossing the Truong Son Mountains, which have long separated the Chinese-influenced north from the Indian-influenced south, we relived that prolonged, supremely tragic war of our youth.

Place names, city scenes and village landscapes all conjured up television images of American bombings and military attacks in the ravaged country.

The wiry toughness, fiery tenacity and innate resourcefulness of the Vietnamese people were evident everywhere we travelled. And there was no residual hostility or acrimony expressed towards us; in fact, it was just the opposite – a friendliness, bluntness and natural curiosity characterised our conversations with the local people.

In Danang, we were moved to tears as hawkers tried to sell us what they insisted were the ‘doggie tags’ of American soldiers slain in the war – for US$1.

In Hanoi, we were charmed by the blend of Chinese, Vietnamese and French architecture, and the tree-lined avenues leading to picturesque lakes, parks, temples and pagodas.

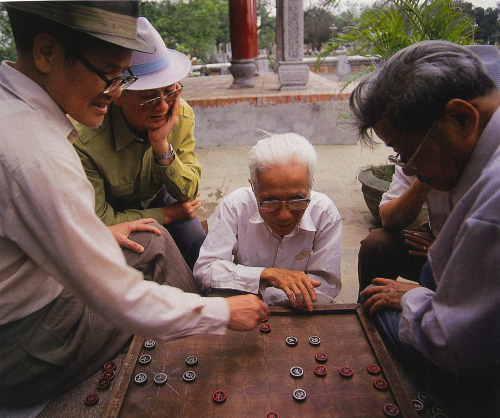

Retirees at a morning game.

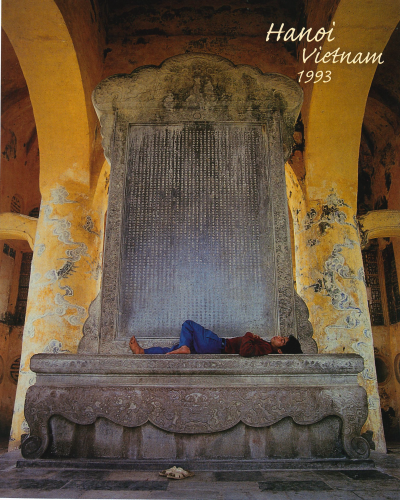

A construction worker takes a lunch-hour nap at Hanoi’s Temple of Literature.

THE PHILIPPINES, 1990

Walking the streets of Manila underlined the very eclectic mixture of Asian and Western cultures that define Filipino contemporary society – from the pre-Christian Indo-Chinese immigrants, to the Arab settlers of the 14th century, to the Spanish colonisers in the mid-1550s, to the American occupation in the late 1890s, Imposing Catholic churches rubbed shoulders with American-style diners and Asian teak houses on stilts.

Driving north to Banaue on Luzon Island revealed the spectacular rice terraces of the Ifugao people, carved into the steep mountains over one thousand years ago – perfectly manicured, emerald green stepping stones to the heavens.

And west of the mountain resort town of Baguio, we got a taste of the archipelago’s tyrannical weather systems; a savage typhoon left us stranded for days, and we finally attempted a drive down the mountain amidst raging rain and mudslides.

Manila: A hungry boy peers through the window of one of Manila’s popular American-style diners.

Banaue: The Ifugao people are expert carvers, though these children abandoned to play seem not to notice the workmanship of their mount.

SIEM RIEP, CAMBODIA, 1997

Strolling the walkways of this stupendous architectural masterpiece, we were in awe of the size, complexity, perfection and seamless symbolism of Angkor Wat – a 12th century replica of the universe in stone, a funerary temple dedicated to King Suryavarman II and a massive devotion to the Hindu gods.

What captivated the most was the Gallery of Bas Reliefs. Full of movement, life, delicacy, beauty and exquisite detail, they came alive before us, recounting epic stories of the Khmer empire at war and the ancient Indian epics. This is a narration that stretches the length and breadth of the temple’s four inner walls – 1200 square metres of carvings, no two exactly alike, each testimony to the Khmer consummate mastery of stone.

The faces of Hindu gods survey the land that gave birth to a great ancient civilisation.

BURMA, 1995

Eyes on the colourful market scene before us, we scrambled into a small boat, from where we would go shopping!

This was the real people’s Floating Market, in the village of Ywana, near the northern Inle Lake. Villagers gathered daily to buy and sell fruits, vegetables, home utensils, fabrics, toys, basketry – whatever comprised their needs for everyday living.

We moved slowly amongst the scores of boats, all jockeying for space, as the hawkers called out their wares and prices – in a singsong type of chant – to passing customers.

But wait – here was a boat crammed with Shan artifacts and crafts where a brass pipe, its spout shaped like a dragon’s head, caught my eye.

Inle Lake: The Ywana Floating Market comes alive with colour and movement.

Budidong: In Burma’s Rakhine State, fishermen prepare for the day’s work in the misty, amber-stroked river.

Yangon: Revellers during Thingyan, the Burmese New Year, have just been thoroughly doused by maidens bearing spouting hosepipes. The fun-filled festival mixes raucous, free-for-all water-throwing with quiet, devotional moments when offerings are made in temples and Buddha images are ritually bathed.

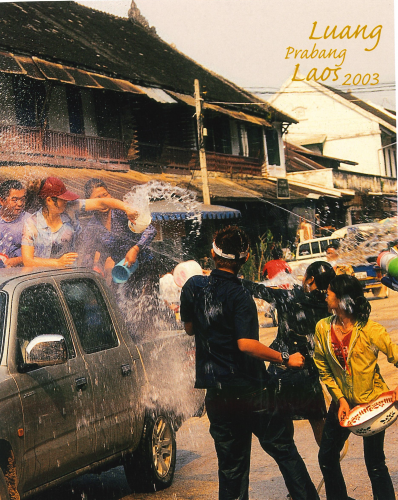

LUANG PRABANG, LAOS, 2003

Encircled by mountains, embraced at the confluence of the Mekong and Nam Khan Rivers, the World Heritage Site of Luang Prabang features gleaming, temple-lined streets, traditional wooden houses – clustered still in the 14th century plan around local temples, intact French provincial architecture, and lantern-lit night markets over-flowing with gorgeous hand-woven fabrics.

Several of the city’s historic temples are examples of the classic Lan Xang (Lao) and Lanna (northern Thai) styles, featuring multiple roofs sweeping low to the ground, heavy exterior and interior embellishment and eyelid-shaped entrances.

The sumptuous gold relief doors of Wat Mai Suwannaphumaham.

Songkran – the Laotian and Thai name for the New Year festival – carries the same meaning, rituals and water-throwing merry-making as the Burmese. A leisurely stroll down the street results in water warfare.

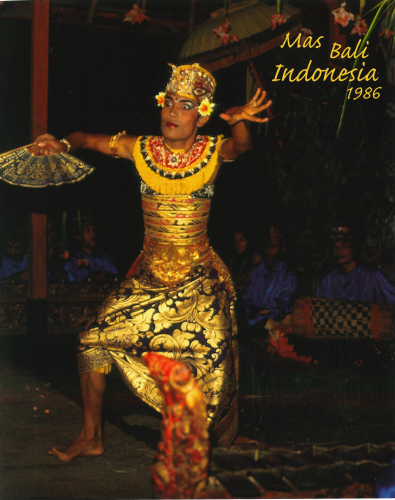

MAS, BALI, INDONESIA, 1986

A car hire took us into the rice-terraced rural areas of this exotic, fabled isle. It is Kuningan, one of the most important religious festivals in Bali, marking the end of a ten-day period of purification when ancestral spirits descend from heaven to dwell again in their families’ homes, and to receive their offerings.

On a village path, women carrying towering trays of offerings – some two metres high – processed to their multi-tiered, stone and thatch Hindu temples. Here purification rituals were performed, prayers were recited and the balance between good and evil was restored.

Later, elaborate music, dance and drama performances entertained the devotees.

Women in procession carry beautifully arranged offerings to their temples.

At a temple in Mas, a male dancer performs the ‘Bumblebee Dance’.

SUMATRA, INDONESIA, 1988

Wandering the pathways of Samosir Island, which sits within Sumatra’s Lake Toba – South East Asia’s largest lake and the seat of the Batik people’s culture – we happened upon a large village wedding.

Most guests were dressed in their hand-woven and embroidered finery. Their attention was focused on the bride and groom who knelt before the village elder performing the nuptials.

The custom of blanket-giving was performed, as one by one the guests placed an intricately woven blanket on the shoulders of the bride and groom. They had to press closer together, else the blankets would not rest squarely on both of them. The custom symbolised the close union and the new life they would now share.

The blankets start to pile up, as the bride and groom receive gifts and blessings from their relatives and friends.

SULAWESI, INDONESIA, 1988

Sitting on the balcony of our small guest house in Tanatoroja’s largest town, Rantepao, on Indonesia’s largest island, Sulawesi, we spotted a procession and quickly decided to follow it. In an instant, we were drawn into the elaborate funeral ceremony of the Toroja people. It comprised a very colourful procession led by decorated buffaloes, other-worldly music, the sacrificial slaughter of pigs and buffalo, and all-day feasting and rituals lasting for several days.

An old woman watches the funeral procession from the window of her tongkonan, a traditional wooden house with wildly soaring roof and painted panels depicting buffalo designs.

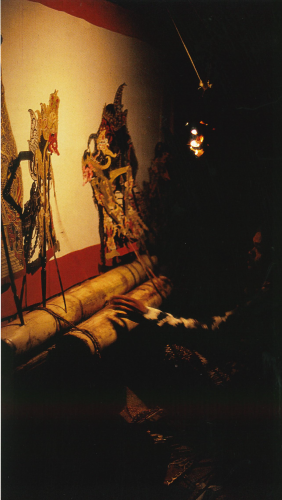

JAVA, INDONESIA, 1985

Of the many rich and multi-faceted expressions of Javanese culture, the shadow puppet theatre Wayang Kulit captivated us the most. Perhaps no other culture in the world places so much emphasis on a theatrical form to transmit values, morality and aesthetics than the wayang.

Essentially mystical in outlook, the Javanese use the Wayang Kulit to explore such themes as the balance between the positive and negative forces in life, the maintenance of internal and external harmony, and the examination of the ideal human being (alus). Scenes and themes derive from the ancient Indian epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, brought to South East Asia in the first century AD.

Accompanied by the piercing, ephemeral gamelan orchestra, the puppet master simultaneously manipulates the hand-made leather puppets - sometimes as many as one hundred at a time, recites their dialogue and song, and tells the story – all with great embellishment, improvisation, interpretation and humour. He thus becomes performer, teacher, philosopher, priest and, at times, exorcist, demonstrating phenomenal stamina, with some performances lasting through the night.

Puppet master and shadow puppets at a village performance.

ARI ATOLL, KURAMATHI, MALDIVES, 1996

It was just a few steps from our thatch-roofed chalet to the gentle sea. Sitting beside the soft, lapping waves, we were privy to a mind-boggling array of sea creatures.

Moray eels peeked from behind the rocks; lion fish picked around the rocks and coral; star fish were revealed in a rainbow of colours. Yellow Spotted stingrays glided past like ballet dancers.

Plunging now into the amazingly clear water to a coral reef literally teeming with fish in the thousands, and my eyes have been opened to the extraordinary beauty and the heart-stopping excitement of exploring the underwater world.

Sky and sea fuse on a dreamy afternoon.

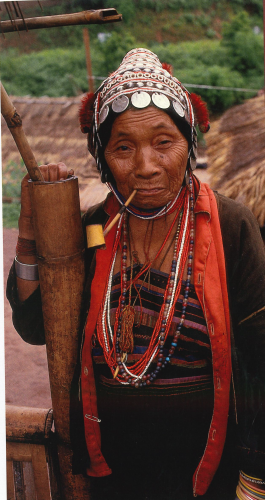

CHIANG MAI, THAILAND, 1985

We were following the crowd – several thousand strong – who were making a pilgrimage up the mountain to the sacred temple Wat Phra That Doi Suthep.

It was the eve of Visakh Puja, the most important day of the Buddhist calendar marking the birth, death and enlightenment of Lord Buddha.

As each person reached the statue of Chiang Mai’s most revered monk, flowers were laid before the statue, candles were placed in a bronze bowl, incense was stuck in a ceramic pot, and gold leaf was laid on the statue. Hands pressed together in the ancient wai – a gesture of veneration and respect – one by one the people uttered their devotions.

Young devotees make offerings for Visakh Puja.

A trishaw driver transports his young passengers to school.

The rich ethnic diversity of northern Thailand is seen in its mountainous villages. An elderly Akha woman in the village of Mae Salong - still wearing the traditional attire of black cotton clothing and silver headpiece, enjoys her pipe.

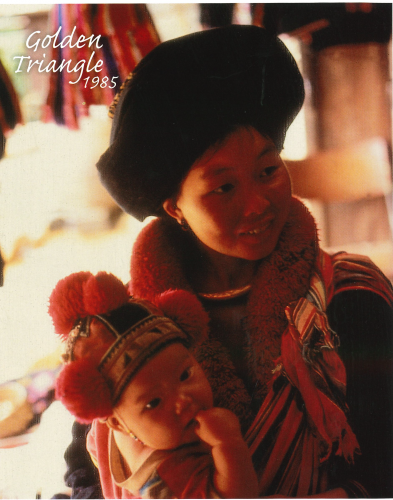

At Mae Salong, a Yao woman tenderly cradles her baby.

© copyright by Linda Pfotenhauer

Photos by Allen Pfotenhauer

Excerpted from the book Reflections, author Linda Pfotenhauer