Recently, my daughter - Jessica Joy Mehta Itumeleng, aged 28 years - asked me to name the five people who had inspired me the most in my life. This was part of a Storyworth book project which she had given me for Mothers’ Day.

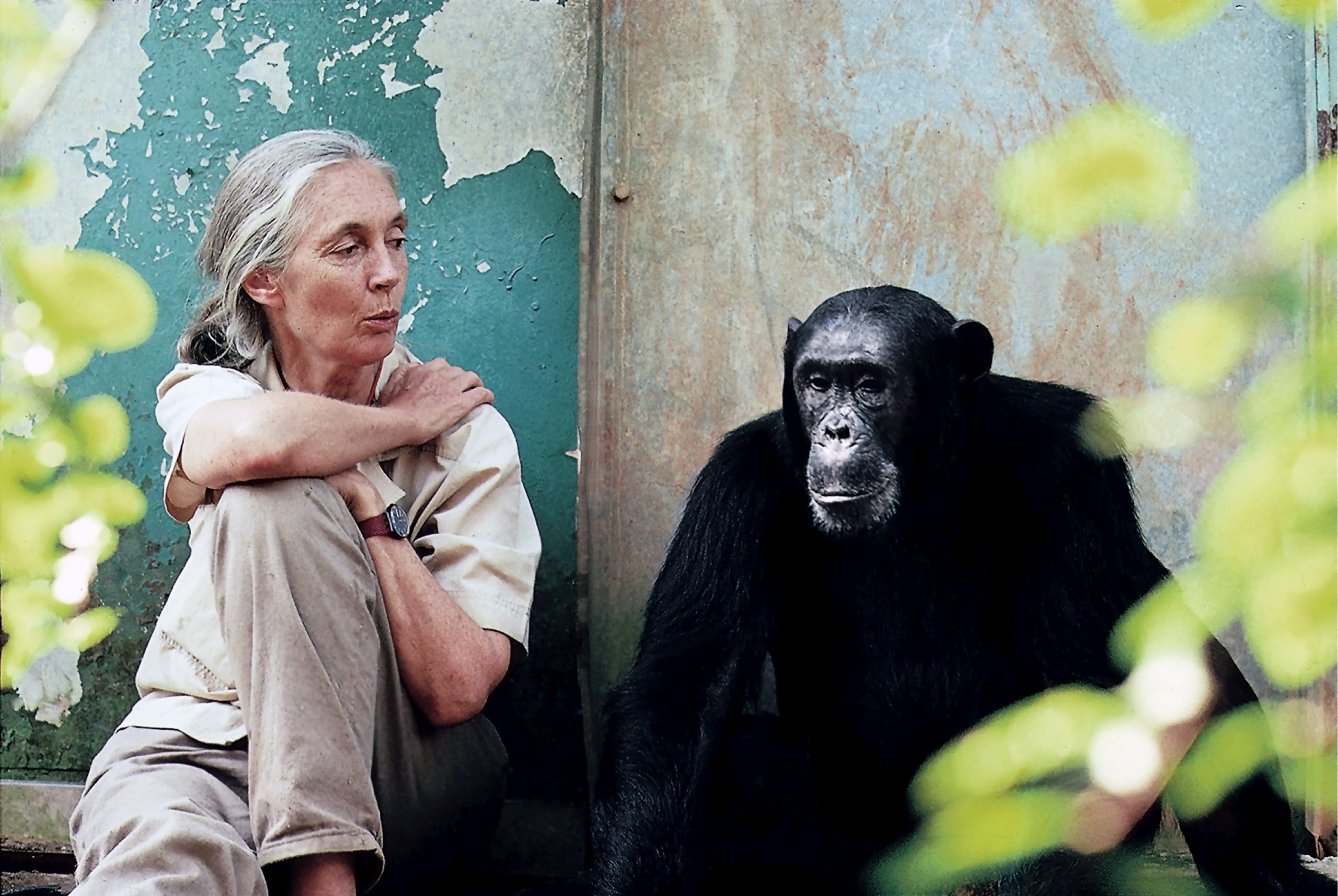

I hesitated not a second to name the first on my list, and responded in an instant - the world renowned primatologist/conservationist Dr. Jane Goodall.

It is fitting to mention Dr. Goodall at this time, as this month (April, 2024) she celebrates her 90th birthday. She is being feted around the world for her pioneering primate research, and her ceaseless conservation projects and education campaigns, which now span 70 years. She is still going strong.

Dr. Goodall's life embodies the very qualities women need to attain professional success: resilience, perseverance, determination, inventiveness, self-confidence, boldness, patience, and an unshakable belief in one’s heart’s dream. She is an icon for conservationists, but more she is an icon for women’s empowerment. And her story comes from deep in the jungles of East Africa. Hence she is also a woman’s voice of Africa.

From the early days of her childhood in England, a young Jane held a deep love of animals and a dream to work with them in Africa. Her parents could not afford to send her to university; so she enrolled in a secretarial course, then landed a job as secretary for a film company in London. She worked as a waitress to earn money for her first passage to Africa. Upon her arrival to Nairobi, aged 23, with her dream before her, she boldly asked for an appointment to see the world famous paleo-anthropologist, Dr. Louis Leakey.

Dr. Leakey and his wife Mary had conducted ground-breaking studies in human origins in East Africa. This spurned his interest in the great apes, believing that an understanding of them would help to understand prehistoric man. He wished to sponsor primate research in Africa.

Upon meeting Jane, he was convinced she was the right person to conduct research on the chimpanzees of Tanganyika (now Tanzania), despite her young age, and her lack of formal education or training. He then embarked on the necessary fund-raising; and by 1960 Jane was installed at a camp in the Gombe Stream Reserve. Government officials would not allow a woman to live alone in the reserve, so Jane’s mother, Vanne Morris-Goodall, always an unwavering support for her daughter, accompanied her as chaperone.

“This was the life I had always wished for,” Jane was quoted as saying in a National Geographic documentary.

From the start, Jane followed her instincts to carry out this most unique project; she eschewed conventional scientific research practices in a number of ways. It took her months of following the chimpanzees before they would allow her presence near them. She endured all manner of physical challenges: snakes, parasites, insects, malaria, and the sheer discomforts of travelling on foot in the bush, up and down foothills, in the intense tropical heat, or rain, for hours every day.

Her first discoveries are by now legendary; and eventually caused the scientific community to redefine human beings. Previously, homo sapiens was believed to be the only animal to make and use tools. Jane discovered that chimpanzees make and use tools, as she watched and recorded one of the older males in the troop she was following pick a twig off a tree, strip it of its leaves and insert it in a termite mound to pull out termites for a meal.

Likewise, traditional scientific belief was that humans were the only animals to have personalities and feelings. Once again, with time, Jane proved this to be fallacious, recording and filming in great detail the emotional lives of chimpanzees.

There were many other discoveries to follow, as Jane established the Gombe Stream Research Center in 1965, and continued her research there for many years. The center grew in size and renown, and hosted other researchers to study chimpanzees there.

As Jane began to write up her field research, she was met with skepticism from the scientific community, who were doubtful about this young woman who had only a secretarial certificate and no university education. The science establishment was primarily men, who at first did not take her seriously. (At that time, women were discouraged from pursuing careers in science.) Potential patrons sought control or concessions, which Jane diplomatically refused.

According to one National Geographic article (October, 2017), Jane’s approach was to ignore the slights and tolerate fools, making sacrifices to sustain her work.

Eventually Jane attained a PhD degree at Cambridge University; and a lecture she gave at the Zoological Society of London in 1962 established her as a respected voice in her field of study.

In the 1990s, witnessing the plight of the chimpanzees and wild animals (largely caused by deforestation, human encroachment, loss of habitat and poaching) and the alarming decline of the health of the planet, Dr. Goodall embarked on a life of advocacy for conservation. “It has become apparent that I have to use this power to help the creatures who have put me in a position to do just that,” she said. She began her now renowned ‘Roots and Shoots’ program, eventually to be established in over 70 countries.

Over the years, Dr. Goodall has established several sanctuaries for chimpanzees, guided and mentored young researchers, written dozens of books, and has been the subject of more than 40 films. Significantly, she has set up and continues to lead conservation projects and education programs in over 100 countries around the world. She is a tireless traveler, giving speeches, lobbying governments, setting up projects and visiting schools. Even now, at her advanced age, she travels over 300 days per year in her conservation efforts, bringing always messages of hope and peace.

An extraordinary woman who broke gender, scientific, institutional, national and cultural barriers.

A remarkable example for those of us who wish to break barriers and follow our dream.

AN AFRICAN AFFAIR

“I hope you have an experience that alters the course of your life because, after Africa, nothing has ever been the same.”

Suzanne Evans, journalist and politician

My own introduction to Africa began in a similar way to Dr. Goodall’s. After an introductory trip to Kenya in 1975, I felt an enamored connection to the land, the animals, the people, and a communication with Nature which I had hitherto never felt so profoundly. Africa had got into my heart and soul.

I began to read everything I could find on the continent: history, travel, people, folklore, anthropology, archaeology, wildlife, conservation, African fiction writers.

Chancing upon some books on the San (Bushmen) of southern Africa, I became fascinated with these original inhabitants of the continent, their way of life, their rock art, their religion. I wished to explore my connection with these people whose culture stretches back to the Middle Stone Age. I developed an inexplicable desire to spend time with them, and in particular to explore their folklore and mythology.

I knew instinctively I had to go to Botswana, where a good proportion of the San people still live today. Though I had no formal training in ethnography, or conducting research, I pressed ahead.

As with all developments in our lives that speak to our life work and destiny, things began to quickly fall into place.

I was able to get a contract to teach at a new secondary school in Letlhakane, a large village deep in the Kalahari Desert; and in 1978, I departed for Botswana.

Unbeknownst to me at that time, the San lived in settlements around the village. But, upon my arrival, I was at a loss as to how to find them and interact with them.

A ‘chance’ (or destined) meeting with a young man who knew where several of these San settlements were, who spoke their language (as well as Setswana and English), and who was willing to work as my interpreter quickly set the project in motion.

As this was an independent project and I did not have much money, we conducted our interviews completely on foot, after school hours and on weekends. The desert sun, heat and sand were definite challenges to make our jaunts adequately uncomfortable. Language was another, until I picked up a bit of Setswana. And of course, becoming familiar with an African people and their culture was a third challenge.

The San groups we came to know were remarkably open and willing to share their lives and their stories. Soon others in the village got to know that I was collecting mainane (traditional folk tales) and came forth with their stories.

By the end of the year, I had accumulated a body of work substantial enough to write two reports on the San of Letlhakane: one on their folklore and religion, another on their socio-economic status. The following year these reports were published by the Botswana Government Remote Area Development Office. They have since been cited in academic papers and books on the San, and at conferences on indigenous peoples.

The introduction to village life in Botswana – the day to day village jaunts and interactions with people – brought an understanding of rural life in Botswana that remained with me, and was useful to me, throughout the next 45 years of living and working in the country.

After marrying and moving to the capital, Gaborone, in 1980, I was hired by the Botswana Ministry of Education In-Service Training Unit to write readers for primary school students (12 of which were published by Macmillan, Botswana).These were meant to be environment and culture specific, and to introduce students to reading as a pleasurable activity, rather than as something only to be mastered for school studies. These stories (45 in all) were mostly informed by my experiences of village life in Letlhakane.

Many other jobs followed in writing and publishing in Botswana over the next 45 years – indeed one seemed to lead to another almost effortlessly: managing editor of the Air Botswana magazine (1980s and then again for 15 years in early 2000), magazines and books for the Botswana Tourism Organization, guide books to Botswana, tourism books, more children’s books, scriptwriting for Botswana TV, consultancies for the UN, SADC, ACHAP, EU, the Botswana Society, the Botswana Government, and many more.

These were tremendously educational experiences for me, rich, varied, for the most part professionally and personally fulfilling and satisfying. And as one project led to another, I began to develop a deep knowledge of – and love for – the country.

When I look back now, over nearly a lifetime of work in Botswana, what do I see? What are the lessons learned? How do I distill the many professional experiences into something coherent and understandable to others?

THE CHALLENGES

“I attribute my success to this: I never gave or took any excuse,” Florence Nightengale

We women face a particular set of challenges, often defined by culture and society, which differ dramatically from our male counterparts. In addition, we are up against the same challenges faced by men. A double whammy!

Chauvinism, Sexism

In many countries around the world, overt chauvinism, particularly in the workplace, still exists. In others, it is no longer acceptable; but latent or hidden chauvinism lingers. There is sometimes an attitude that ‘oh, it is a woman; she won’t be up to the task”, when usually the female worker achieves higher than her male counterparts. Unfortunately, the scenario of male bosses expecting sexual favors from female employees persists.

Head-to-head confrontation often has a negative impact. Hence the best course of action is to work very hard, achieve high, and prove your worth. Employers value honesty, reliability and steadiness, which shows your value. Ignore snide comments or jokes, or disturbing underlying attitudes, and simply get on with the work. This is the approach I have found that works best.

Office Intrigue

Jealousy in the workplace is a common problem. It usually involves hurtful comments and rampant gossip; and sometimes it goes further where colleagues conspire to viciously tear you down. In that case, the workplace becomes toxic and almost unbearable.

Here too the best course of action is often (but not always) to ignore the gossip and negativity, get on with the work, and see the jealousy as the other person’s problem, not yours. Often an appropriate act of kindness or compassion can turn off such cruelties. Never let others see that their behavior is disturbing you. Easier said than done, I know!

Nepotism

This is an almost impossible nut to crack. In most cases you won’t win. Better to search for another job!

Motherhood and Children

Those of us who know the joys of motherhood also know the frustrations and conflicting emotions of being either a single, working mom or a married, working mom.

We perform a delicate balancing act, finding enough time – and energy – for work demands, and our children’s needs. We want so much to be there for them, but work may dictate otherwise.

I doubt there isn’t a working mom alive who has not felt the pangs of guilt when, for instance, we cannot be present for a child’s school recital, in favor of an important office meeting, or we cannot be home with the child when he/she is sick.

Women excel at multi-tasking; and this working moms do in abundance. Sometimes we feel we are being pulled in so many different directions. And it exhausts us.

What I have found over the years, in the time-stressed, deadline-dominated world of journalism and publishing, is to remain extremely organized, and to work off three weekly ‘to-do’ lists: home and food, work and child. I usually put the child’s list first, but this may not be possible for some.

Any form of exercise -- a walk, swim, yoga, dance, zumba, a visit to the gym -- is a tremendous stress reliever, as well as a ticket to mental and physical good health. I have always tried to find time to make this an integral part of my day, and my life.

I have also found it essential to create regular blocks of time set aside for children, family and myself – and to keep them sacrosanct. Sunday, for example, should be a complete break from all the ‘busyness’, a time to relax with family and, if possible, get out in Nature.

Mistakes

Botswana’s beloved the late Mr.Gobe Matenge - a towering figure of public service and one of the architects of the country’s independence – once told me in an interview: “Mistakes are good. We learn from them. And we build our successes from them.”

How right this wise old man was.

Take your mistakes as important lessons to be internalized and understood. See what you have done wrong, and work to make it right in the next effort.

In fact, I would go so far as to not call them ‘mistakes’ at all. Rather they are necessary stepping stones, on the path to success.

THE ESSENTIALS

“It always seems impossible, until it is done.” Nelson Mandela

My nearly half century of working in my chosen field of journalism, writing, editing and publishing has driven home certain often-heard but nevertheless crucial truisms. These echo the example set by Dr. Goodall.

Success follows when we listen to our inner voice. This voice speaks of our destiny, and why we have been put on this Earth. Following our instinct is critical in setting and achieving goals.

The satisfaction lies in the effort, not necessarily in the achievement.

It is all in the ‘doing’.

Success is facilitated by:

+Positivity

+Hard work

+Perseverance

+Determination

+Flexibility

+Resourcefulness

+Self-confidence

+Strength

+Resilience

+Planning

+Preparation

+Genuine interest in colleagues, their lives and problems, and a willingness to help where needed

And perhaps most important of all – LAUGHTER!

Keep that sense of humor. Keep the jokes flying. Don’t take yourself so seriously!

ENJOY LIFE!

We are indeed extraordinarily blessed and privileged to have this marvelous life on Earth!

© copyright: Linda Pfotenhauer